Prof Lilley and Dr Kane - the historic mapping of Ireland and place names

Looking inside the names

The landscape of place-names that we see around us in Ireland today span at least a 2000-year history and reflect the various languages spoken in Ireland over the centuries: Norse, French, English, Scots, and particularly Irish (as the majority of names are of Gaelic origin). These names were often recorded for the first time following the English conquest and colonisation of various parts of the island.

For the most part, names and extents of lands were preserved in oral memory before the arrival of the Anglo-Normans, who introduced a bureaucracy concerned with the possession and transfer of conquered lands. A great number of Irish place-names, particularly those of an administrative nature are first and only ever recorded in English sources, and via this process reflect the conventions of English and are therefore obscured, sometimes beyond recognition.

One of the lasting legacies of the 19th century Ordnance Survey (OS) in Ireland is also associated with this process of language transfer documentation – the reshaping and standardisation of new townland names for inscription on its maps. Names, and the recurring elements within them, originally of Irish language origin were therefore rendered more compatible with the orthography and pronunciation of contemporary English in the 19th century:

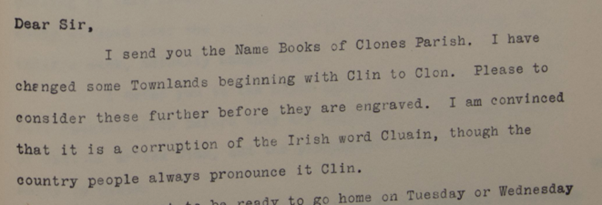

An extract from a letter written by John O'Donovan in 1834 to OS Headquarters in Phoenix Park, Dublin where he documents the standardisation of the place-name element cluain 'meadow', despite being clearly aware of different pronunciation in the locality. O’Donovan produced The Ordnance Survey Name Book, parish-by-parish alphabetical listings of the place-names that were to become the standardised English versions on the first OS 6” maps.

A significant proportion of elements in contemporary Irish-place names can be identified as deriving from noteworthy features of the landscape, such as hills (cnoc, anglicised 'knock'), rocks (carraig, anglicised 'carrick'), valleys (gleann, anglicised 'glen') islands (inis, anglicised 'inish'), and rivers (abhainn, anglicised 'owen'). As time went on, more places were named after man-made features, such as churches (teampall, cill, anglicised 'temple' and 'kil-'), forts (lios, dún and ráth appearing as 'lis', 'doon/down' and 'ra/raw') and bridges (droichead, appearing as droghed/drohid). These elements often also appear alongside qualifying components, such as names (family names, personal names, names of saints or mythological legends), and adjectives such as mór 'big/great' or beag 'small/little'.

Once referred to as 'the great betrayal' in which Irish place-names were 'reduced to whispering husks', this process of transition has, at times, been seen as a process by which native names were corrupted and destroyed. Friel, who based his own 'Translations' on the OS project in Ireland, being of the view that ‘new placenames were put on those maps...the towns and villages were given anglicised names – a whole country was rechristened’, despite the fact that the Ordnance Survey in Ireland represented just one stage of the anglicisation of place-names, which began in earnest with the Anglo-Norman conquest.

And indeed, the state of linguistic flux within which Irish names have been coined since earliest written records (and before), has left us with a multi-layered name-scape that testifies to long-standing contact between populations, tongues and traditions. By tracking the evolution of a place-name from administrative documents (such as those produced at the time of the OS) we can read the story of the land in a very unique way.

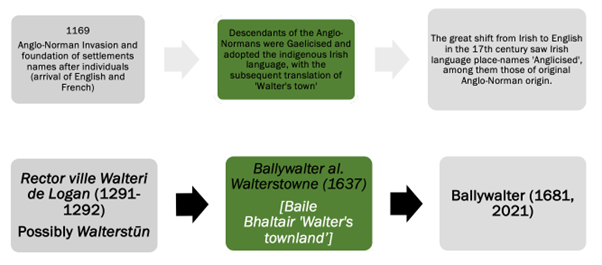

Consider, for a second, Ballywalter (in Co. Down), which was originally coined in English by the Anglo-Normans, but was subsequently Gaelicised and Re-Anglicised as the language of its inhabitants shifted over generations:

The emergence of the contemporary form of the parish and townland name of Ballywalter, Co. Down. that the first shift, from the English alias identified as Walterstowne (indicated as an alias form in 1637) involves a direct translation, and the emergence of the equivalent Irish language form Baile Bhaltair 'Walter's town(land)'. Historical data from placenamesni.org

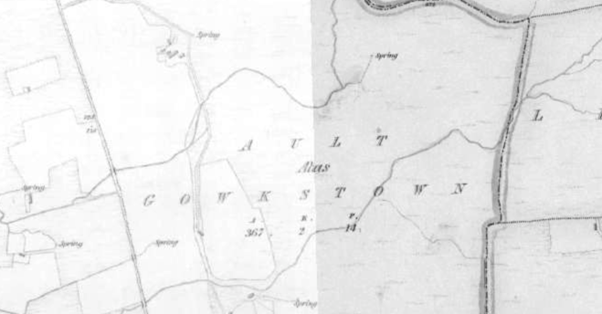

Of course, such layers of language in our place-names is not restricted to those that have emerged as a result of the centuries-long dance between Irish and English. Scots spread to Ulster during the great period of migration in the early 17th century, and Scots elements have nestled themselves quite comfortably alongside those that were already in use, often as an alias name. In the case of Ault Alias Gowkstown in Co. Antrim, the English name of the townland seems to be older than the Irish. The 1734 estate survey identified the lost name Ballymcveagh (Bellymakveagh), probably originally a larger area, with Gowkstown, the name used in 1782, 1812, and 1880. The form with its origins in Irish, Ault (Allt ‘ravine’) appeared first on Lendrick’s map, 1780.

Excerpt from Ordnance Survey (OS) County Antrim first edition, showing the townland of Ault Alias Gowkstown. Gowk is the Scots for ‘cuckoo’ but O’Donovan suggested in the Ordnance Survey Name Books that in this case it was a surname. Map image from PRONI Historical Maps Viewer: https://apps.spatialni.gov.uk/PRONIApplication/

One only needs to scratch the surface of the place-names in use in contemporary Ireland to discover a myriad of interesting language mixes and calques, influenced by language contact, language shifts and transfer of names both across populations and down generations. The place- names around us encode within them a record of past environments and so constitute a significant strand of intangible cultural heritage. In exploring the multilingual nature of our place-names, there is great potential to empower individuals and communities to countenance greater tolerance of contemporary linguistic diversity.

The Northern Ireland Place-Name Project was established with such empowerment in mind in 1987; since then it has worked to deepen the engagement of the public with names as a manifestation of shared languages and shared space.

Dr Frances Kane, Queen’s University Belfast

The Northern Ireland Place-Name Project [placenamesni.org]

Looking behind the map

The earliest and most detailed mapping of Ireland’s townlands is now nearly two hundred years old. In 1824, the Ordnance Survey began its work creating a new series of maps covering the whole island at the large scale of six-inches to one-mile. This was an ambitious undertaking, and Ireland was the first country in the world to be entirely mapped at this scale.

Looking at the Ordnance Survey 6” maps of Ireland offers us a snapshot of the landscape as it was just before the arrival of the railways. The surveyors were interested in ensuring their maps were as accurate as possible, and especially for determining the boundaries of the ancient townlands. This was in fact the main purpose of the survey, to help reevaluate the taxes levied through the size of each townland, so accuracy in measurement in the field was important.

Out ‘in the field’, the surveyors journeyed across the whole of Ireland, from north to south, over a period of thirteen years, between 1829 and 1842. The final 6” maps were published in 1846. The surveyors’ trace across the Irish landscape is also plotted out by the maps they helped to create. Each 6” map sheet has on its margins information on those men who surveyed the ground, and then engraved the map for printing. This gives each map its own ‘biography’ and links the map itself back into the field where its features were surveyed in such detail and with such accuracy.

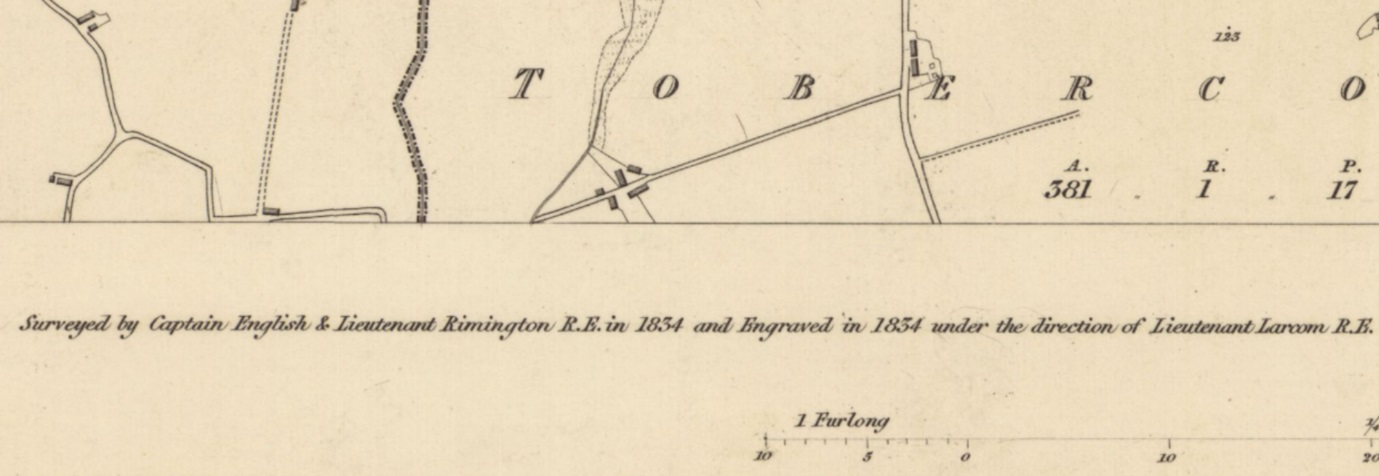

Marginal information on County Down sheet 37, naming the surveyors as Captain English and Lieutenant Rimington (Royal Engineers). ‘A.R.P.’ written underneath the townland name (Tobercorran) indicates the calculated townland area (in acres, roods, perches). Surveyed: 1834, engraved: 1834, printed: 1837. Size: map 61 x 92 cm (ca. 24 x 36 inches), on sheet ca. 70 x 100 cm (28 x 40 inches). Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland (https://maps.nls.uk/view/246835403)

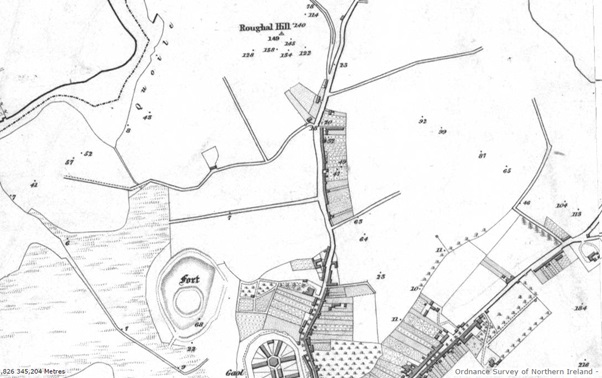

A close look at the 6” OS map shows a range of landscape features, from roads and settlements, to rivers, loughs, buildings, woodland and parkland. They are a sight to behold, beautiful to look at, so carefully executed with the engravers work reflected in the carefully drawn lines and the neat writing, all there to see on the finished map. While of course there are still controversies about the forms of the place-names that appear on the map, the 6” maps themselves ‘tidy up’ the Irish landscape, for all maps are selective, and partial, in what they show.

There is one special characteristic feature too of the first edition series of the OS 6” maps of Ireland. A distinctive trait is a trail of dots, organised in straight lines, criss-crossing the map. These dots on the map represent the trails through the landscape taken by the OS surveyors in the field. They are called ‘chaining lines’ and a close look at the map shows these lines radiate out from ‘trigonometrical stations’. One of the first tasks of the OS surveyors in the field was to create a series of triangles across the landscape, a ‘trigonometrical network’. Each triangle was measured in the field by an accurate and precise instrument, a theodolite, and on the 6” map a triangle symbol with a dot is used to show where the theodolite was set up by the surveyors.

Looking across the 6” map we can see numerous trigonometrical stations shown, each a reminder of where the surveyors stood in the landscape to make their observations. About a century after the survey, one of the director generals of the OS, Sir Charles Close, reflected on this arduous task, writing “From trig point to trig point the chain was dragged….”. The field operations of the OS that underpinned the 6” maps were indeed hugely laborious. The surveying equipment had to be manhandled across bog, mountain, and pasture, across the landscape. Those dots on the map—the chaining lines—show where the surveyors trudged, joining up their trigonometrical stations with measurements of heights and distances, to show on the maps the rise and fall of the land, to give a sense of relief. Contours on OS maps came later.

So now, two hundred years later, when we look at the first edition of the 6” OS maps, we should try to see ‘behind the map’, to the field. It was in the field the maps were made, wrought from the landscape by specially trained military men, commanded by Thomas Colby. The trigonometrical stations and chaining lines on the maps stand as testimony to this huge endeavour, made all the more poignant this year—in 2024—the bicentenary of the start of the Irish Ordnance Survey.

Prof Keith Lilley, Queen’s University Belfast