Looking inside the names with Dr Frances Kane

The landscape of place-names that we see around us in Ireland today span at least a 2000-year history and reflect the various languages spoken in Ireland over the centuries: Norse, French, English, Scots, and particularly Irish (as the majority of names are of Gaelic origin). These names were often recorded for the first time following the English conquest and colonisation of various parts of the island.

For the most part, names and extents of lands were preserved in oral memory before the arrival of the Anglo-Normans, who introduced a bureaucracy concerned with the possession and transfer of conquered lands. A great number of Irish place-names, particularly those of an administrative nature are first and only ever recorded in English sources, and via this process reflect the conventions of English and are therefore obscured, sometimes beyond recognition.

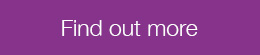

One of the lasting legacies of the 19th century Ordnance Survey (OS) in Ireland is also associated with this process of language transfer documentation – the reshaping and standardisation of new townland names for inscription on its maps. Names, and the recurring elements within them, originally of Irish language origin were therefore rendered more compatible with the orthography and pronunciation of contemporary English in the 19th century:

An extract from a letter written by John O'Donovan in 1834 to OS Headquarters in Phoenix Park, Dublin where he documents the standardisation of the place-name element cluain 'meadow', despite being clearly aware of different pronunciation in the locality. O’Donovan produced The Ordnance Survey Name Book, parish-by-parish alphabetical listings of the place-names that were to become the standardised English versions on the first OS 6” maps.

A significant proportion of elements in contemporary Irish-place names can be identified as deriving from noteworthy features of the landscape, such as hills (cnoc, anglicised 'knock'), rocks (carraig, anglicised 'carrick'), valleys (gleann, anglicised 'glen') islands (inis, anglicised 'inish'), and rivers (abhainn, anglicised 'owen'). As time went on, more places were named after man-made features, such as churches (teampall, cill, anglicised 'temple' and 'kil-'), forts (lios, dún and ráth appearing as 'lis', 'doon/down' and 'ra/raw') and bridges (droichead, appearing as droghed/drohid). These elements often also appear alongside qualifying components, such as names (family names, personal names, names of saints or mythological legends), and adjectives such as mór 'big/great' or beag 'small/little'.

Once referred to as 'the great betrayal' in which Irish place-names were 'reduced to whispering husks', this process of transition has, at times, been seen as a process by which native names were corrupted and destroyed. Friel, who based his own 'Translations' on the OS project in Ireland, being of the view that ‘new placenames were put on those maps...the towns and villages were given anglicised names – a whole country was rechristened’, despite the fact that the Ordnance Survey in Ireland represented just one stage of the anglicisation of place-names, which began in earnest with the Anglo-Norman conquest.

And indeed, the state of linguistic flux within which Irish names have been coined since earliest written records (and before), has left us with a multi-layered name-scape that testifies to long-standing contact between populations, tongues and traditions. By tracking the evolution of a place-name from administrative documents (such as those produced at the time of the OS) we can read the story of the land in a very unique way.

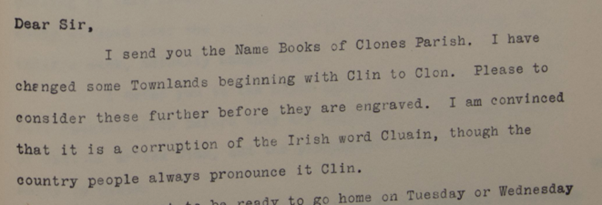

Consider, for a second, Ballywalter (in Co. Down), which was originally coined in English by the Anglo-Normans, but was subsequently Gaelicised and Re-Anglicised as the language of its inhabitants shifted over generations:

The emergence of the contemporary form of the parish and townland name of Ballywalter, Co. Down. that the first shift, from the English alias identified as Walterstowne (indicated as an alias form in 1637) involves a direct translation, and the emergence of the equivalent Irish language form Baile Bhaltair 'Walter's town(land)'. Historical data from placenamesni.org

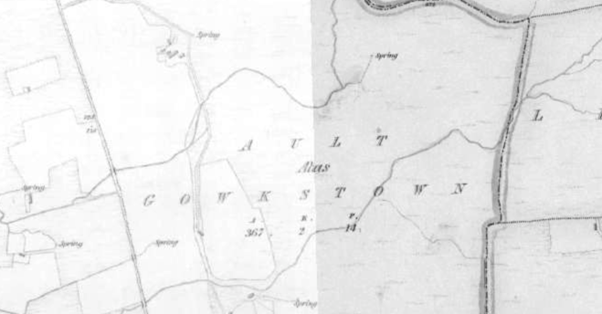

Of course, such layers of language in our place-names is not restricted to those that have emerged as a result of the centuries-long dance between Irish and English. Scots spread to Ulster during the great period of migration in the early 17th century, and Scots elements have nestled themselves quite comfortably alongside those that were already in use, often as an alias name. In the case of Ault Alias Gowkstown in Co. Antrim, the English name of the townland seems to be older than the Irish. The 1734 estate survey identified the lost name Ballymcveagh (Bellymakveagh), probably originally a larger area, with Gowkstown, the name used in 1782, 1812, and 1880. The form with its origins in Irish, Ault (Allt ‘ravine’) appeared first on Lendrick’s map, 1780.

Excerpt from Ordnance Survey (OS) County Antrim first edition, showing the townland of Ault Alias Gowkstown. Gowk is the Scots for ‘cuckoo’ but O’Donovan suggested in the Ordnance Survey Name Books that in this case it was a surname. Map image from PRONI Historical Maps Viewer: https://apps.spatialni.gov.uk/PRONIApplication/

One only needs to scratch the surface of the place-names in use in contemporary Ireland to discover a myriad of interesting language mixes and calques, influenced by language contact, language shifts and transfer of names both across populations and down generations. The place- names around us encode within them a record of past environments and so constitute a significant strand of intangible cultural heritage. In exploring the multilingual nature of our place-names, there is great potential to empower individuals and communities to countenance greater tolerance of contemporary linguistic diversity.

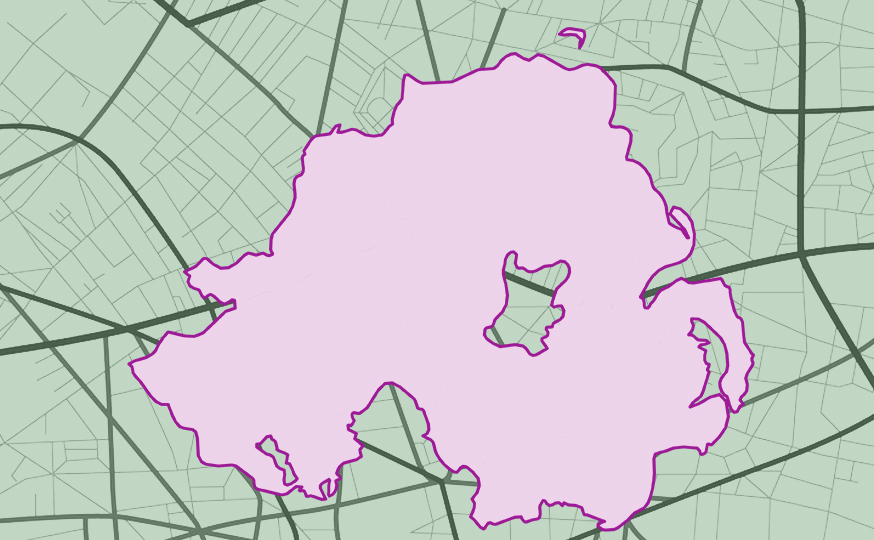

The Northern Ireland Place-Name Project was established with such empowerment in mind in 1987; since then it has worked to deepen the engagement of the public with names as a manifestation of shared languages and shared space.

Dr Frances Kane, Queen’s University Belfast

The Northern Ireland Place-Name Project [placenamesni.org]